|

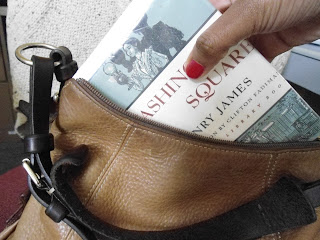

| I love books that can fit into my purse! |

The novel is set in pre-Civil War New York. It’s a New York before new money and robber barons invaded society and changed things forever. It’s an era, actually, before that of Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country. The novel is a very insular novel (in fact, it even seems as if most of the novel takes place indoors). There are only a handful of characters, but because of this we can focus intensely on them. Washington Square is the story of Catherine Sloper, a New York heiress of average looks and personality (that’s her main point, it seems). A pauper named Morris Townsend wants to marry her, and Catherine’s father, Dr. Sloper, thinks Morris is a golddigger. Dr. Sloper is absolutely right about Morris’s motives and character, but, as Fadiman points out, “to be right is not enough.”

Henry James uses first person a great deal—he writes “I,” “we,” and “our.” This really brings the reader into the story, and makes it seem as if James is sort of an old friend who’s telling us this interesting story. The conversational tone is constant (which makes me happy—constancy in using a literary device is a virtue). When Dr. Sloper wants to take Catherine to Europe in order to distract her from her, Henry James writes, “Catherine had many farewells to make, but with only two of them are we actively concerned.” There is something really endearing about that.

The psychology of the novel is fascinating to me. Dr. Sloper and Mrs. Penniman (Catherine’s aunt) pretty much stunt Catherine’s growth. Both are unlikable, but Dr. Sloper’s sarcasm is a little funny (but sad, ultimately, as it usually comes at the expense of his own child). He is an intriguing character, and his conversation with Morris Townsend provides some amazing dialogue from Henry James. Dr. Sloper wants to bend Catherine to his will, and is amused to discover that she has a will of her own. It’s hurtful that he has such a low opinion of his daughter (maybe this was common for fathers at this time…if so, that’s pretty unfortunate). And Mrs. Penniman is downright inappropriate…weird, truth be told. She wants the relationship between Morris and Catherine to be a great love story, and sticks her nose in where it certainly doesn’t belong in order meet this goal. She’s irritating, creepy, and crosses a lot of boundaries (if only therapy were around for our dear Catherine). Catherine, we are constantly told, is dull and unremarkable. But in the end I came to admire her. Mrs. Almond, Catherine’s other aunt, seems to be the lone person with common sense, but because she minds her own business, we don’t hear much from her corner.

Great passage: There was something hopeless and oppressive in having to argue with her father; but she too, on her side, must try to be clear. He was so quiet; he was not at all angry; and she, too, must be quiet. But her very effort to be quiet made her tremble.

Up next: I decided that I need more Henry James in my life, so I am going to pick up The Portrait of a Lady again—and finish it!

|

| A quote on one of my tea bags by Henry James's brother William |

No comments:

Post a Comment